TYLA: The Foreign With A Faulty Engine

Entitled Uppity African or Demure Pop Princess? Let's Take It There.

The smell of Sol de Janeiro and hookah filled my nostrils as I sipped on a passionfruit mimosa. In the background of the Silver Spring brunch spot, I heard the autotuned whisper, “Make me sweatttttt.” I pulled out my phone and started doom-scrolling while waiting for the waitress to return with our food. Getting me out of the house has been a tough feat since COVID, but I promised a friend I’d meet her at this Amapiano brunch. As I got back to my phone, I saw Bretman Rock at the top of my feed, skin tan and glowing like a glazed donut, sitting on a boat and lip-syncing, “Make me lose my breath.” Suddenly, I felt the walls closing in on me. Maybe it was my social anxiety, or maybe it was the feeling that I was being attacked from all sides. Tyla’s break-out hit Water seemed to be inescapable. I’d tried my best to avoid her—not because I didn’t like the music, but because every time I saw anything about her, it felt like I was being pulled into the dark hell of online discourse.

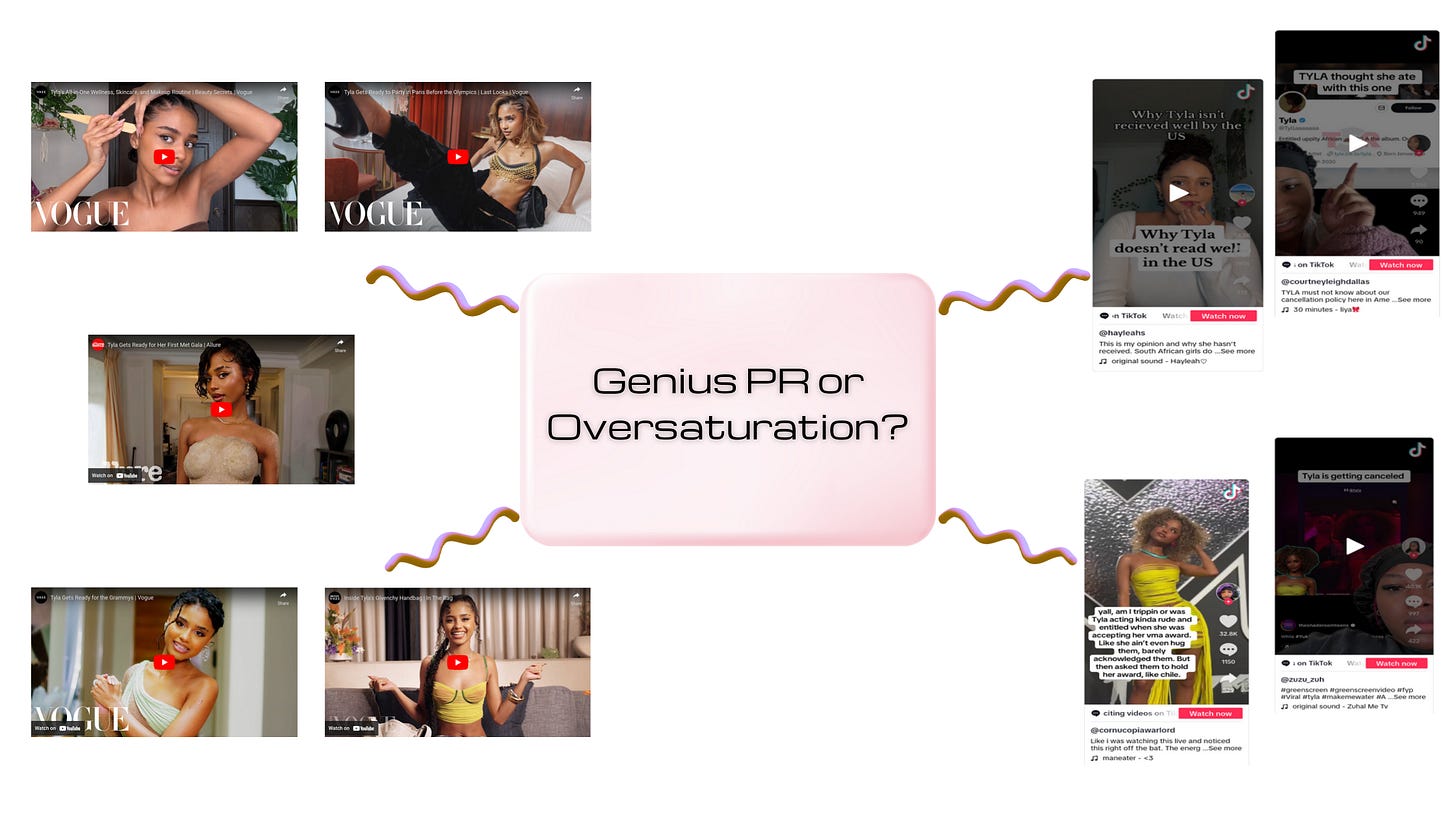

Honestly, Tyla feels a bit like a foreign car with a faulty engine—beautiful, exotic, but stalling just when she should be accelerating. Her career, though meteoric, is struggling to start on solid ground. There are a few factors to consider here. First, the audience can sense the artificiality behind her rise. She has all of these accolades after basically one song. Then there’s the endless, obvious publicity push— late night appearances, Vogue, Allure, it reeks of pay-for-play. Her label is pushing her into the public eye, hoping to manufacture excitement, but it feels forced. And the audience can tell. No one thinks Tyla isn’t talented. She absolutely is. And, honestly, I think people want to like her. The girl is confident, and I love that about her. But that confidence can’t be rooted in positioning herself as better than the very audience she’s trying to win over. Confidence is powerful, but when it’s built on a foundation of comparison and subtle superiority, it turns people off. That’s where she’s losing us.

The thing is, none of us were looking for Tyla. She just showed up one day, almost like she’d fallen out of a coconut tree 🥥🌴. Was it the onslaught of staged paparazzi pictures? The YouTube recommendations of her Vogue GWRM videos? Or maybe it was the endless TikTok videos of people pouring water on their asses. I’m not sure. But what I am sure of is that despite her accolades, her career feels shaky. It seems like the new artist starter pack these days is a Grammy and a canceled tour. This is a stark contrast to when I was little, staying up late to watch Lady Gaga arrive at the VMAs in an egg, screaming to my parents, “I’m not going to bed! This is ART!” Back then, it felt like artists would give anything—maybe even cut off an ear—to prove their devotion to their craft. But now, it feels like our artists have better places to be than on stage. And that’s exactly why people are telling Tyla to exit stage left. For many, it seems that being a racially ambiguous girl with a catchy hook and alluring visuals has become the formula for success. But despite having the formula, there’s still a disconnect between Tyla and her audience.

This brings me to the larger issue: the heightened culture wars, which have been amplified since Elon Musk took over Twitter. Diaspora disputes as I call them, are no exception. “Global” artists like Tyla are constant talking points between African Twitter and Shea Butter Twitter. There’s irony in the name itself—after all, shea butter originates directly from Africa. Yet the constant back-and-forth in the comments and the not-so-hot takes on TikTok, scolding African Americans for their hesitancy to support these artists, always seem to forget one thing: the necessity of boundaries.

Black Americans are the driving force behind popular culture, not just domestically but globally. For centuries, our culture has been ripped from us, exploited, and commodified without our consent. Our influence can be found in every genre—from the viral resurgence of country, rock, and reggaetón, to the global domination of K-pop. Just look at the rise of K-pop groups in recent years—tell me you don’t see them cosplaying as Black Americans, mimicking our style, our swagger, our sound. If there’s one thing music executives know, it’s that you need Black Americans—more specifically, Black American women—to support you. We outspend every other demographic, we dictate the trends. And that’s exactly why Tyla’s positioning of herself in her song Jump feels so gross. Lines like, “He ain’t ever seen a pretty girl from Joburg, see me once, now that’s what he prefers,” hit differently when you unpack the subtext. Who is this “he” she’s referring to? Given the context, we can assume it’s an African American man—after all, if he were South African, he likely would have seen a pretty girl from Johannesburg. And who is Tyla implying that he now prefers her to? The implication here is that he prefers her over American women, specifically Black American women. Although the song is catchy, it’s vibe leaves a sour taste in our mouths due to the undertone of colorism.

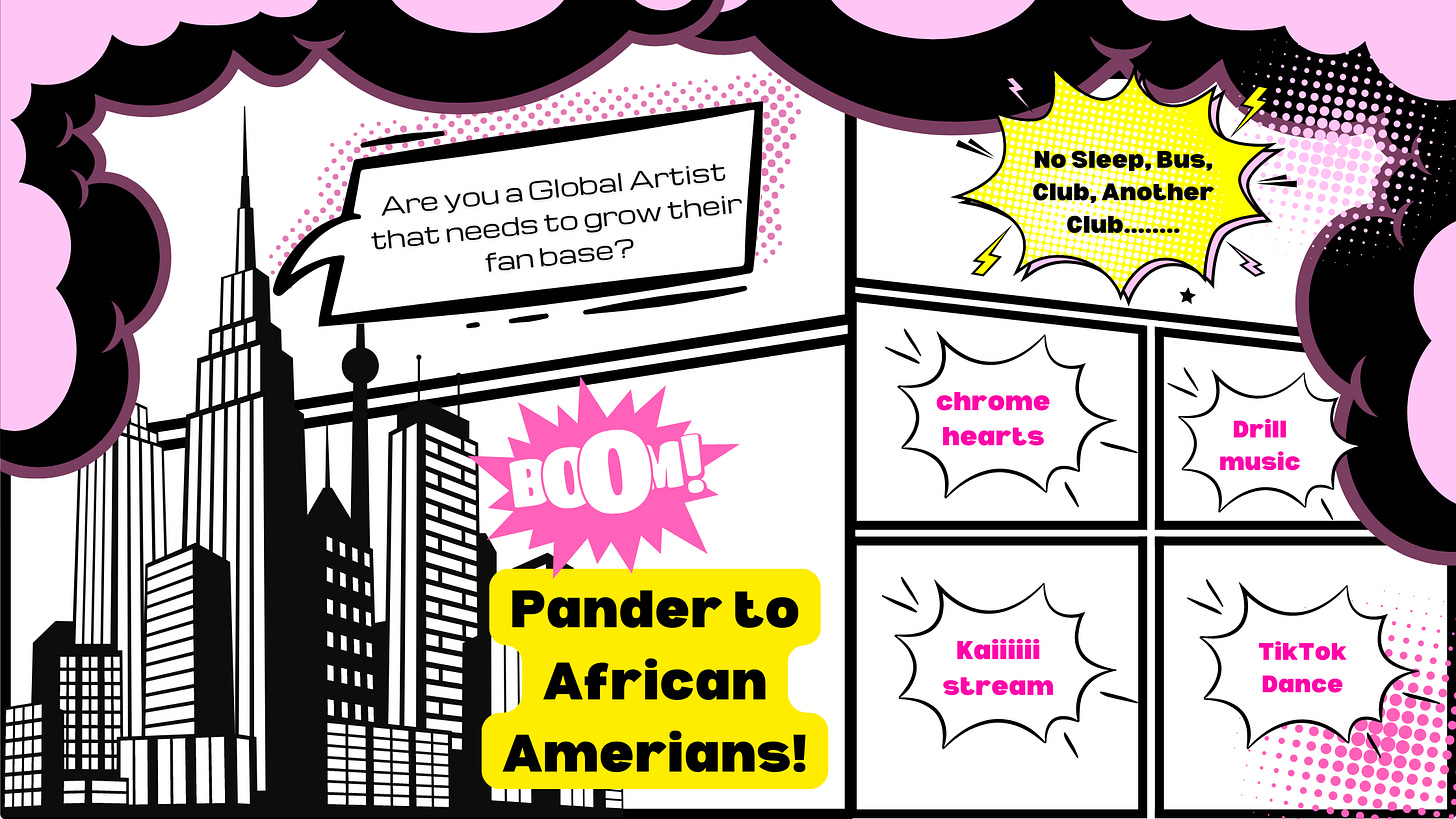

This is what we call subtext. And to ask the audience to ignore it when it’s convenient seems problematic. The issue isn’t that we don’t like Tyla’s music—it’s that we’re trying to get to know her, and it feels like she’s entering our space, asking for our support, while simultaneously disrespecting us. Most “global” artists eventually pander to Black Americans. From Bad Bunny to Burna Boy to Central Cee, aesthetic choices, collaborations, and brand deals are never random. They’re strategically conceived in boardrooms and Zoom calls, aimed at tapping into the cultural lifeblood that is Black American music. So when artists like Tyla come onto the scene, it’s disheartening to see them play into the divide-and-conquer narratives that pit Black people from different parts of the world against each other.

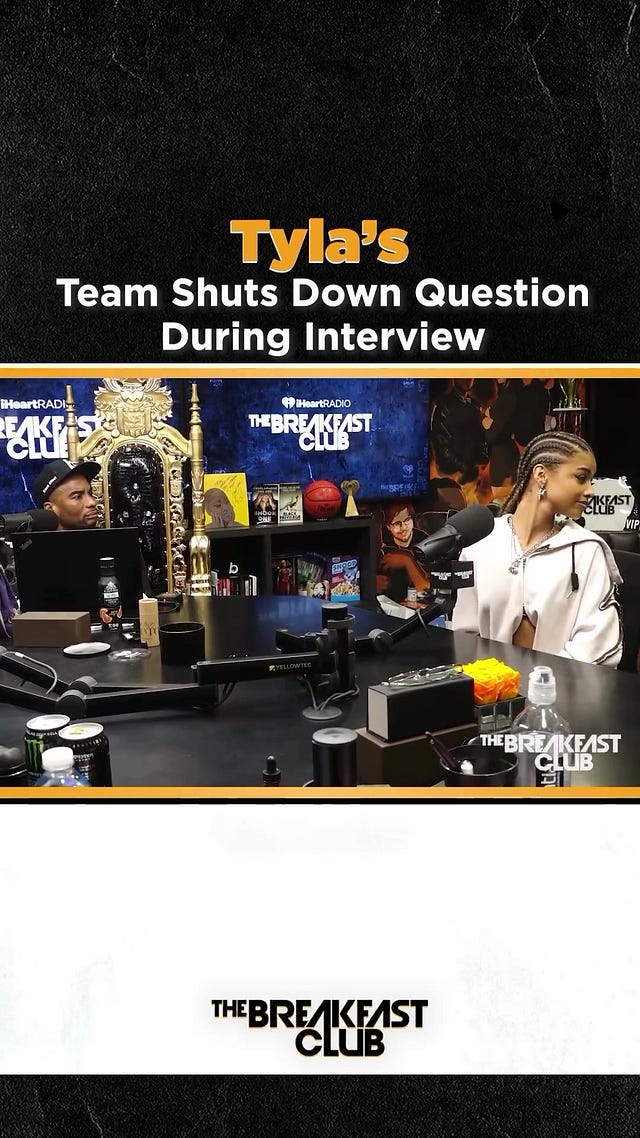

Black Americans are entitled to boundaries. It is a culture has been pillaged for centuries, and that’s exactly why cultural gatekeeping is necessary. We should be allowed to call out hollow attempts at pandering, to protect it. You shouldn’t be able to make one bop, collaborate with rappers, and enjoy the benefits of this culture without showing respect. And that’s exactly what Tyla did. Every time she speaks, there’s an air of condescension that comes off her, whether it’s turning her head toward her publicist when Uncle Charla asked her about her identity on The Breakfast Club, as if the question was beneath her, or when she shooed away her stylist and tried to hand her award to Halle on the VMA stage the other night. But you do have to answer the question, Tyla. When you come into someone’s space uninvited, it’s the least you can do.

Tyla’s identity as a Colored woman from South Africa adds a layer of complexity to the cultural tensions surrounding her rise in America. Charlamagne’s admission of ignorance regarding her Colored identity highlights a gap in understanding, yet it in no way diminishes African Americans’ capacity to discern and navigate the intricacies of racial hierarchies. While African Americans may not be familiar with South Africa’s specific racial classifications, they’re deeply aware of how colorism and preference play out in their own culture. Tyla’s experience as a Colored person—someone historically positioned between Black and White in South Africa’s racial order—parallels how lighter-skinned or racially ambiguous figures often receive preferential treatment in the American music industry. This nuance deepens the sense of disconnect African Americans feel toward Tyla, as her racial identity aligns with global beauty standards that often marginalize darker-skinned women. Her attempt to expand her career in the U.S. is therefore complicated by the cultural baggage she brings, making it harder for her to authentically engage with a Black American audience already sensitive to issues of colorism and representation.

Cultural gatekeeping isn’t exclusionary—it’s a strategy of self-preservation in a world where Black resources are constantly commodified. The argument that Tyla shouldn’t have to identify herself racially makes sense if she stayed in her own Amapiano bubble. But she didn’t. She crossed over and is trying to sell something. So when you come into our house, tell us the truth about your product. The fact is, her music wouldn’t sell the same where she’s from. That’s not an insult; it’s just the reality of marketshare. Thats why her label is spending millions of dollars pushing her in this market.

The retort to the criticism is to say that Black Americans don’t understand the complexities of racial hierarchies and can therefore in no way understand Tyla’s racial identity. That is delusional. We’ve lived with the one-drop rule, the paper bag test, and countless other oppressive systems designed to classify and divide us. This led to the phenomena of “passing” and created hierarchies within our communities. White supremacy works the same way across the world, and South Africans are not immune to the psychological manipulation that separates us.

The problem with Tyla isn’t that we misunderstood her racial identity—it’s that her attempts to connect with Black American audiences felt disingenuous. And when her marketing strategy got clocked, it threw African Twitter into shambles. Instead of acknowledging the gimmicky branding and suggesting she pivot or lean into her own culture, they gaslit Black Americans for trying to establish boundaries. So, let’s take it there: Africans often look down on African Americans, treating them like the cousin you try to distance yourself from because you’re embarrassed by their life choices. Instead of focusing on the common enemy—white supremacy—we argue amongst ourselves about things that don’t matter. And until we can close this cultural gap, the Tylas of the world will continue to remind us of the anti-Blackness Black Americans face daily.

The cultural divide between Africans and African Americans runs deep, rooted in centuries of colonialism, exploitation, and white supremacy. The term "Entitled Uppity African," now being thrown at Tyla, reveals the complex layers of tension between these communities, shaped not just by geography but by class, historical trauma, and the manipulation of racial hierarchies. This label is not just a casual insult—it carries with it the weight of deeply ingrained classism, where African immigrants are often perceived as looking down on African Americans. The roots of this are tied to historical perceptions of opportunity and respectability, where some African immigrants see themselves as having "earned" their place in Western society through hard work, education, or by avoiding the stigmatized markers of African American culture. In contrast, African Americans are burdened with the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and systemic racism, struggles that have historically shaped their identity and created a different relationship to both whiteness and Blackness.

To understand this tension, we must revisit the Middle Passage, the brutal crossing of enslaved Africans to the Americas. This journey not only forcibly separated African peoples from their homelands, it also planted the seeds of a relational gap that persists today. The Middle Passage symbolizes more than just the physical distance between Africans and their descendants in the Americas; it represents the psychological and cultural disconnection that white supremacy has carefully cultivated. Enslaved Africans were stripped of their languages, customs, and identities, forcing them to create a new culture in the Americas, while those who remained on the continent continued to evolve their own societies under the pressures of colonialism. This divide, born of a shared but divergent trauma, set the stage for the misunderstandings and judgments we see today. Africans and African Americans have been conditioned to view one another through a lens distorted by centuries of exploitation and manipulation.

White supremacy operates by dividing groups of color, pitting them against one another to maintain control. It views Blackness as a monolith, flattening the rich and varied experiences of Black people across the globe into one reductive, stereotypical narrative. By doing so, it creates fractions within Black communities, encouraging competition and resentment rather than solidarity. The concept of the "Entitled Uppity African" plays into these divisions, feeding the false narrative that Africans are inherently better, more deserving, or more respectable than African Americans, whose fight for survival in the face of systemic racism is seen as less dignified. This idea serves white supremacy by reinforcing the myth that Black people cannot unite, that our struggles are not shared, and that our liberation is not tied to one another.

In reality, the gap between Africans and African Americans is not one of inherent difference, but of perception. African immigrants often arrive in the U.S. or other Western countries with the hope of upward mobility, but they encounter the same systems of racial hierarchy that have long oppressed African Americans. Yet, instead of solidarity, these systems push them to distance themselves from African Americans, to align with the myth of the "model minority" or the "respectable immigrant" who can succeed by assimilating into white norms. This distance is precisely what white supremacy thrives on, allowing it to continue to exploit Black labor, creativity, and culture while keeping us fractured.

The metaphor of the Middle Passage is a reminder that, despite the physical and psychological distances imposed on us, we share a common history of resistance, survival, and resilience. To bridge the divide, we must confront the ways in which white supremacy has conditioned us to view each other through a distorted lens. African Americans and Africans alike must reject the stereotypes that seek to define us, to see through the classist, colorist, and xenophobic narratives that white supremacy has carefully crafted to keep us apart. Only then can we begin to heal the cultural rift that has been centuries in the making, uniting in the shared struggle for justice, equity, and the preservation of Black culture on our own terms.

Tyla has to decide who she wants to be: an artist who stands the test of time by addressing cultural tensions head-on, or just a pretty girl making brunch bops. Either one is okay. Her music is fun, but true artistry is about more than just catchy hooks. The best artists dig deeper, confront hard truths, and evolve. Tyla has the talent—now she just needs to figure out if she’s ready to do the work, or stay surface-level and risk fading out as fast as she blew up. If she’s smart, she’ll start by listening and learning, and let her music reflect that growth.

The Tyla discourse turned me off from her and unfortunately her music isn’t good enough *to me* to override that initial distaste. The Black American community is very accepting even if you don’t identify as Black but we can also tell when someone is looking down on us.

Oooooooooweeee you took it there! And Ariana, i must say, you nailed it!!! I'm soooo proud of your analysis... everything you said was so carefully well thought out, and based in factual evidence!!!!